Using the Science of Reading to Guide Planning for Multilingual Learners

In recent years, the Science of Reading has become a powerful force shaping literacy instruction across the United States. Through state mandates, curriculum adoptions, and professional learning requirements, educators are being asked, and sometimes required, to change how they teach reading. Much of this conversation has focused on early literacy, phonics, and decoding, with elementary classrooms clearly in mind.

As a middle and high school ESOL teacher and coordinator, I have found myself both aligned with and unsettled by this movement.

Aligned, because the Science of Reading is not a program or an ideology. It is research-based practice. At its core, it reflects decades of work on how reading develops, how language functions, and why certain instructional approaches are more effective than others. That matters deeply for multilingual learners, who are too often under-served by vague or unsystematic literacy instruction.

Unsettled, because mandates are not fixes. They create direction and urgency, but they do not teach students. When the Science of Reading is interpreted narrowly or applied without attention to context, multilingual learners, especially at the secondary level, risk being left out of the conversation entirely.

I also think it’s critical that we shift toward research-based practice whenever possible. This article reflects my attempt to find the gold at the heart of the Science of Reading and adapt it thoughtfully for a high school English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classroom, a space where students arrive with very different language histories, educational experiences, and relationships to reading.

The Classroom Context: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

This unit took place in a co-taught high school ESOL class alongside an English teacher. Across two sections, I worked with students from a diverse range of linguistic and cultural backgrounds:

Newcomers with limited or interrupted formal education

Multilingual learners still developing foundational English proficiency

Long-term multilingual learners with IEPs or 504s who speak English fluently but continue to struggle with reading and writing

Some students had experienced war or displacement. Others had spent years in U.S. schools without ever receiving explicit reading instruction aligned to their needs. All of them deserved access to complex, meaningful texts, not watered-down materials presented as support.

This mix matters because it immediately complicates how research-based reading practices are applied. The same strand of instruction that supports one student may be unnecessary, or even counterproductive, for another.

That reality does not invalidate the Science of Reading. It demands professional judgment.

Using the Reading Rope as a Design Tool

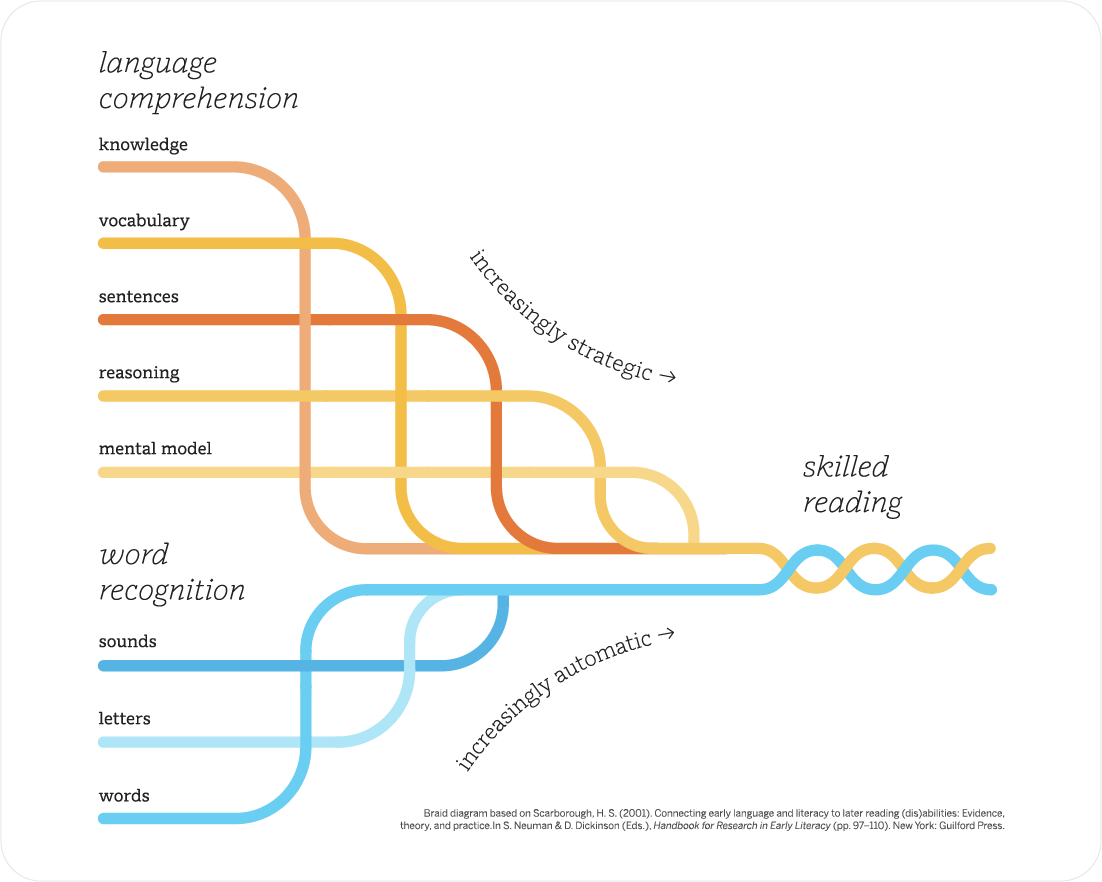

I used this graphic from Amplify to help guide my planning.

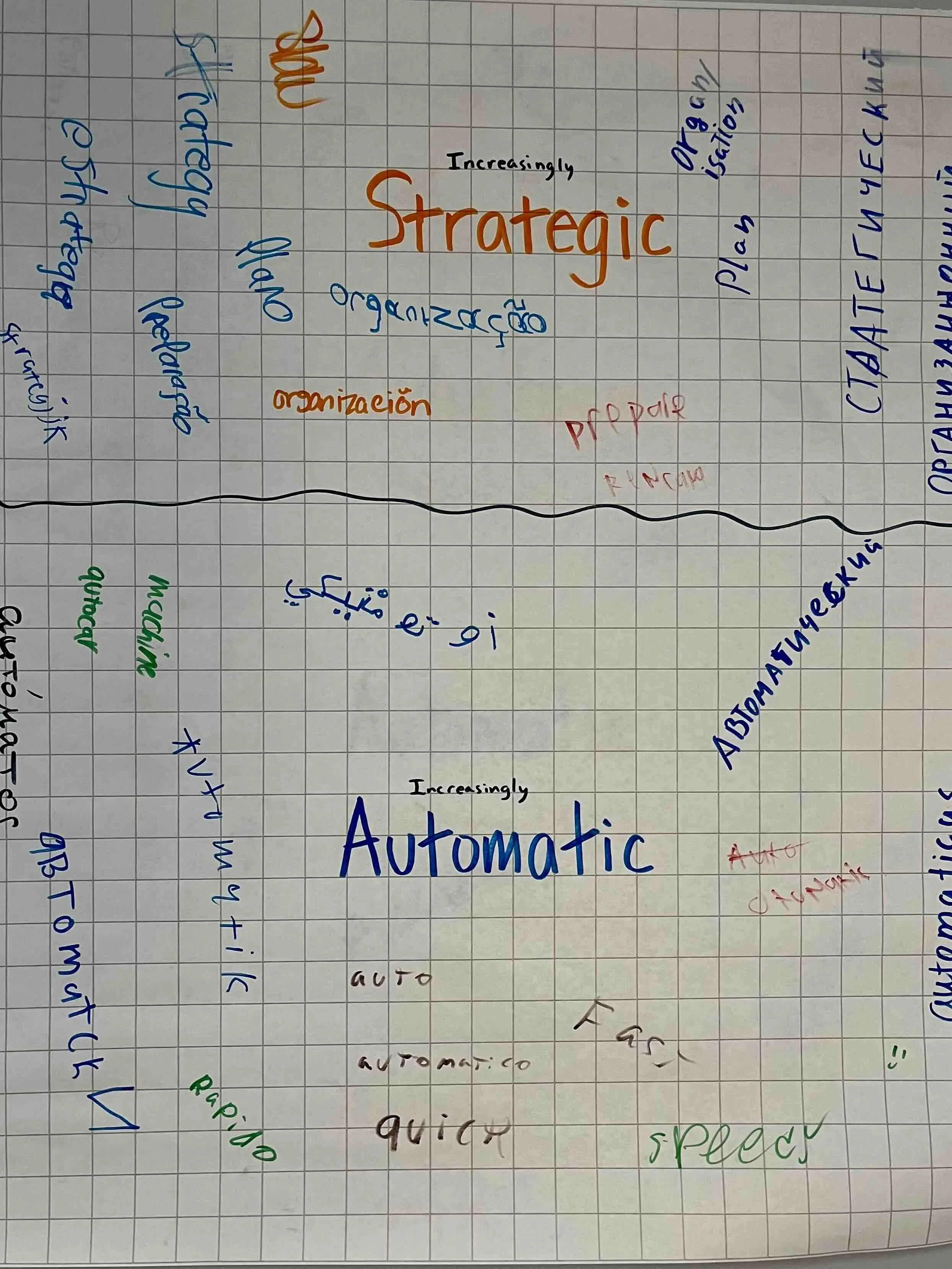

Rather than treating the Science of Reading as a checklist of strategies, I used Scarborough’s Reading Rope as a thinking framework for unit design.

The rope helped me ask better questions:

Which strands matter most for these students right now?

Where do language comprehension and word recognition intersect for multilingual learners?

How do we make reading growth visible when students’ goals differ?

For this unit, I intentionally emphasized language comprehension strands:

Background knowledge

Vocabulary

Sentence structures

Mental models

For some long-term multilingual learners, aspects of word recognition, particularly automaticity with high-frequency words, were still relevant. For most newcomers, decoding English words without sufficient language comprehension would not lead to meaningful reading.

This was not a rejection of the Science of Reading. It was an application of it.

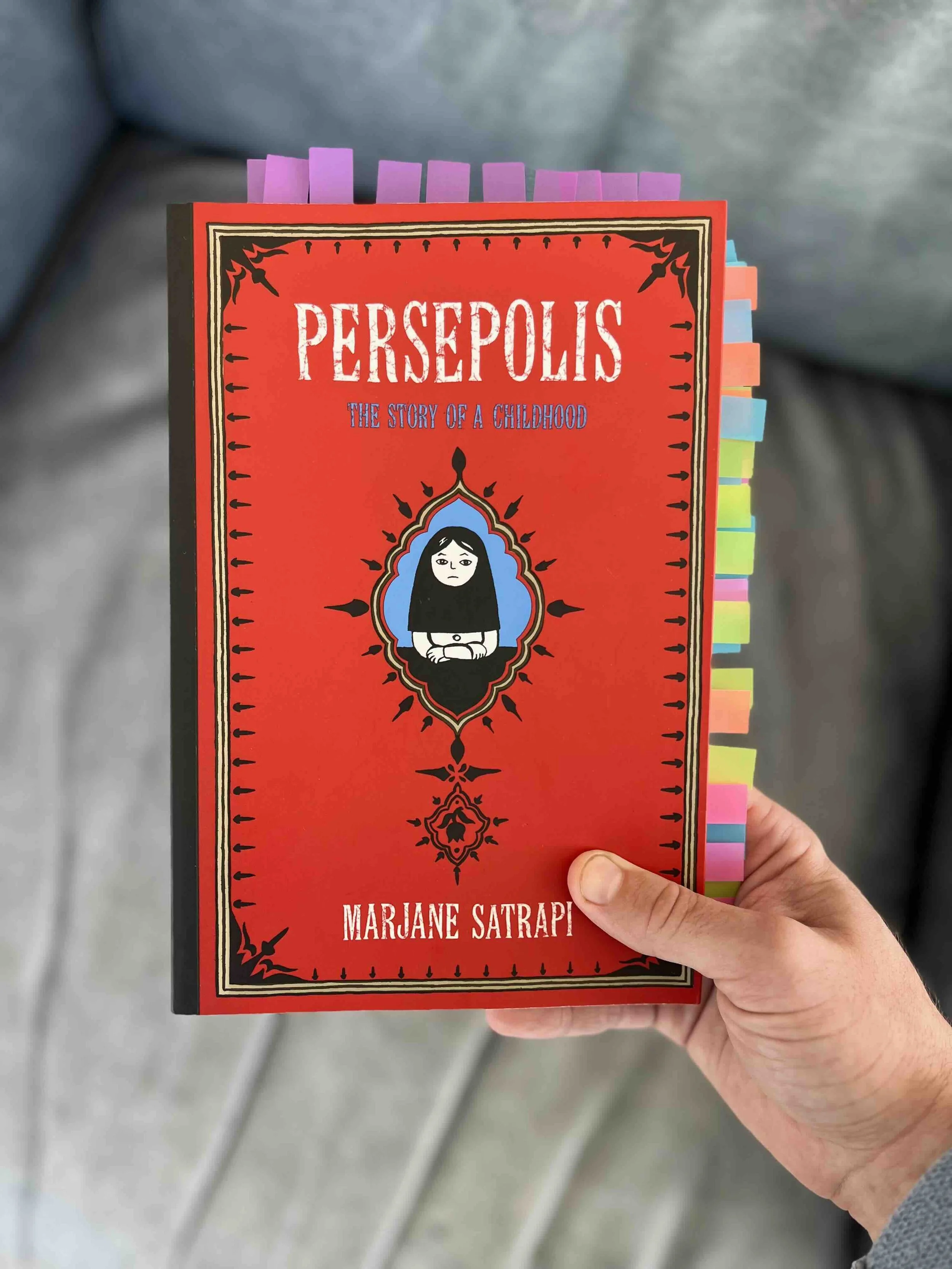

During my first read-through, I marked key vocabulary, moments that required extensive background knowledge, and other potential teaching points.

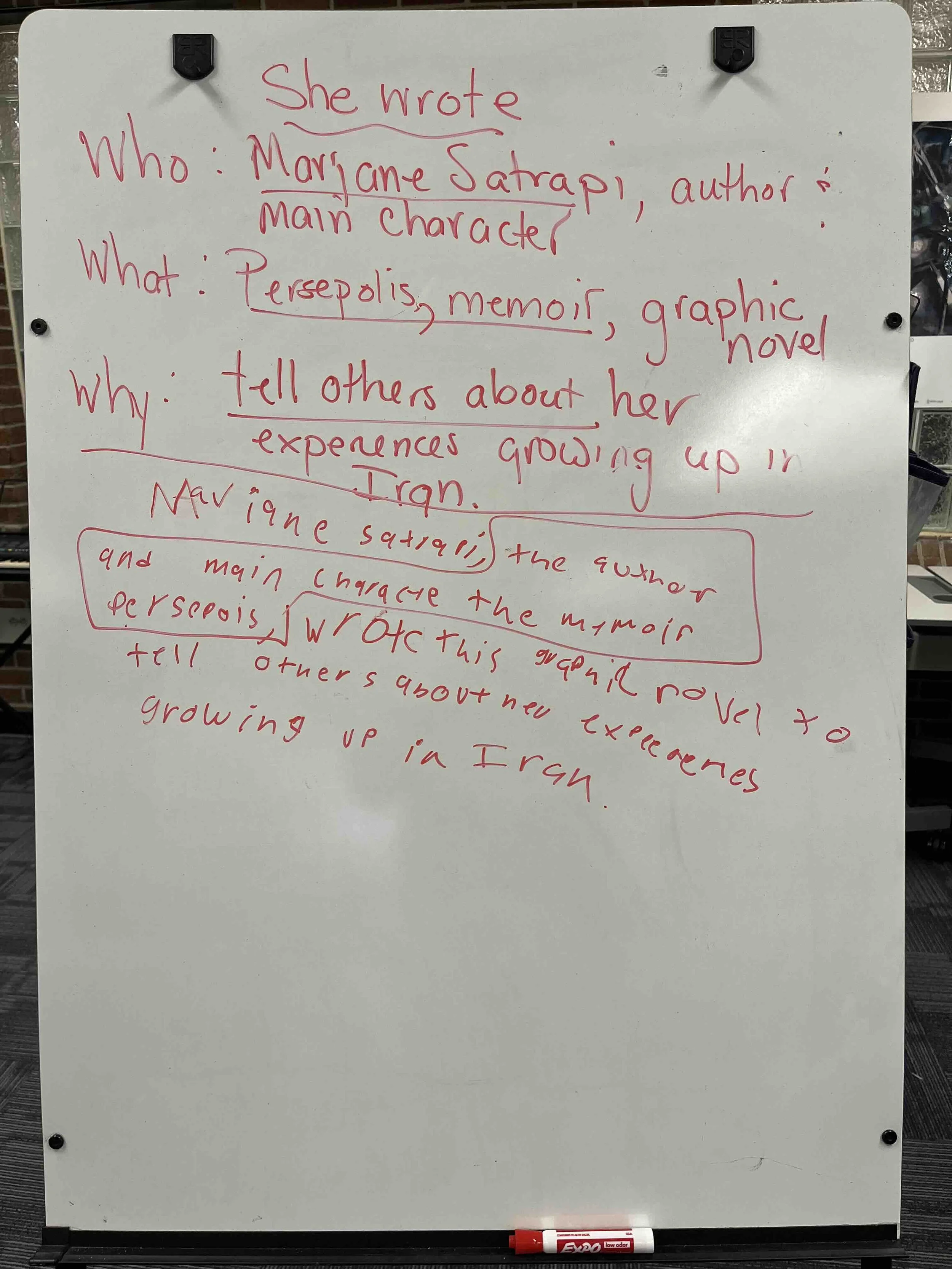

An Accessible, Complex Anchor Text: Persepolis

We anchored the unit in Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, a graphic memoir about growing up during the Iranian Revolution.

Graphic novels are sometimes dismissed as easier texts, but Persepolis offers exactly the kind of complexity multilingual learners need. It presents dense themes related to identity, war, truth, and power. It demands significant background knowledge. At the same time, its visuals support comprehension and invite close reading, inference, and discussion.

We read the text in class. That choice mattered. It allowed us to control pacing, build shared understanding, support newcomers without isolating them, and keep reading communal rather than solitary.

Students encountered challenging ideas together, even when their English proficiency differed.

Sentence-Level Work: Where SoR and ELD Meet

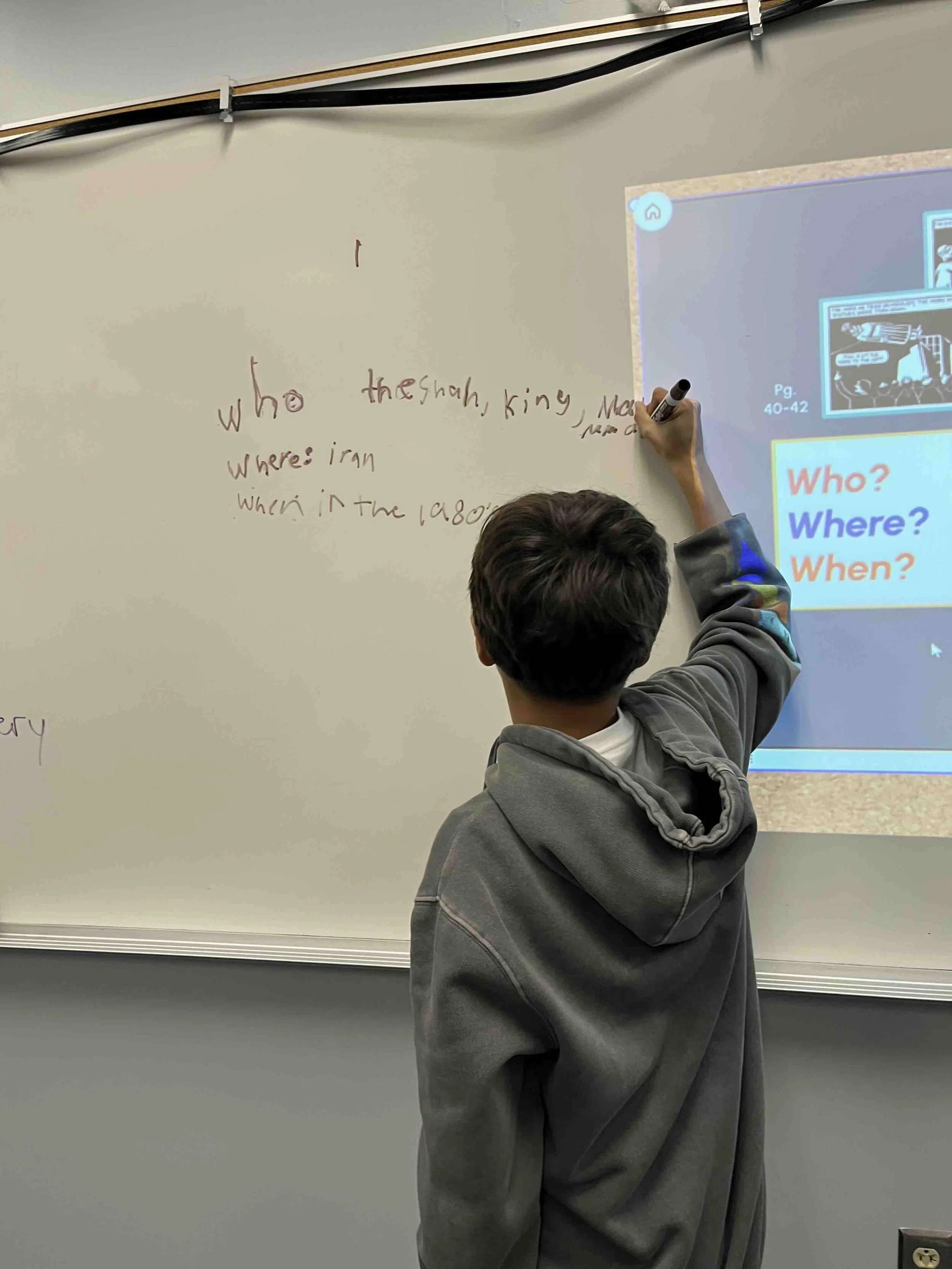

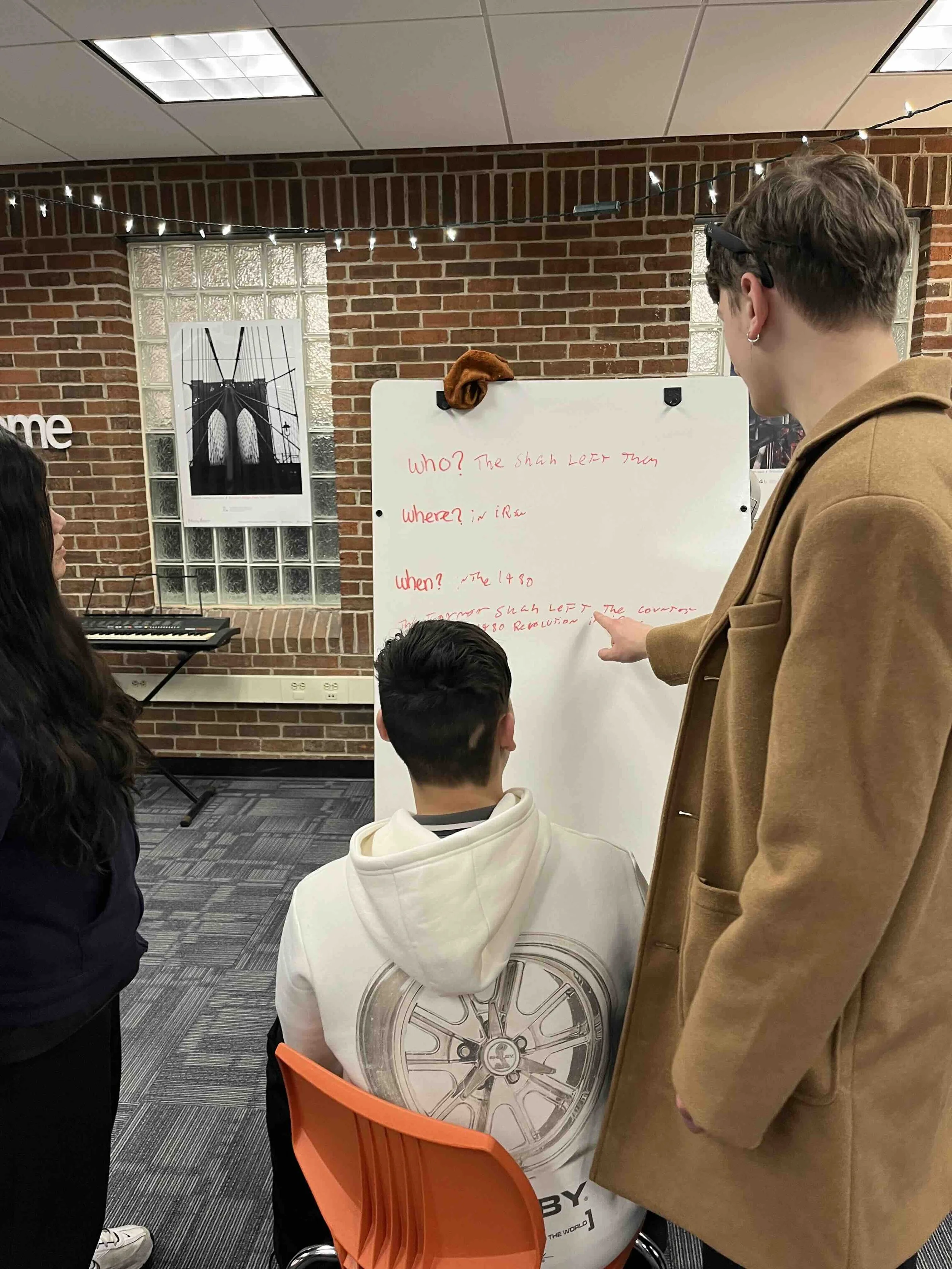

One of the most effective instructional moves in the unit happened at the sentence level.

Borrowing from the Hochman Method, we used sentence expansion to slow down reading and deepen comprehension. Students worked from very short kernel sentences, sometimes just two or three words like “They protested” or “She listened,” and expanded them by answering who, what, where, when, how, and why.

This work did several things at once. It supported syntax development, forced close reading of panels, made inference visible, and gave newcomers a clear entry point. At the same time, it challenged more advanced students to elaborate meaning with precision.

Sentence-level work became a bridge between decoding, comprehension, writing, and speaking. It also gave students a concrete strategy they could return to during assessment.

Reading Goals: Making Growth Explicit

On goal setting day, students completed a word study warm up exercise.

Each student selected two personal reading goals connected to different strands of the Reading Rope. These goals varied. Some focused on building academic vocabulary. Others targeted understanding complex sentences, creating mental models of events, or tracking cause-and-effect relationships.

The process of setting goals was as important as the goals themselves. Students were asked to reflect on what felt hard about reading, what they were trying to improve, and how they would know if they had made progress. Students taped their goals sheet on the inside of their notebook and referenced their goal before reading each class.

We explicitly taught students the words “demonstrate” and “tangible” and reminded them every day that they were expected to demonstrate tangible progress on their reading goals. This re-framed reading growth as something observable and personal and gave students the vocabulary to reflect on their progress using academic language.

AI as Tutor: An Experiment, Not a Solution

Throughout the unit, we experimented with an AI tool, NotebookLM, as a way for students to support their reading goals.

The results were mixed. Some had success using NotebookLM to build background knowledge and practice writing different sentence types using Tier II vocabulary. Others struggled to ask precise questions, use the tool efficiently, and transfer AI-generated explanations back to the text. At first glance, this could be read as failure. I did not see it that way.

This difficulty served as a data point. It showed how much scaffolding independent learning actually requires. It reinforced that AI does not replace comprehension. It also made clear that using AI effectively is itself a literacy skill.

Rather than abandoning the experiment, we treated it as part of the learning. Students reflected on when AI helped, when it did not, and why.

In a unit centered on preparation vs. protection, this partial “failure” with AI led to some great four corners discussions. Shielding students from AI would not prepare them for the world they are entering. Unleashing it without guidance would not either.

Writing as Evidence of Reading

The unit culminated in an argument responding to the question: What motivates people to hide difficult truths from others?

This writing task was the reading assessment. Students were expected to use evidence from Persepolis, apply sentence strategies, incorporate vocabulary from their notebooks and word walls, and demonstrate progress toward their reading goals.

For some students, growth showed up as correct verb tense, clearer sentences, or accurately using new vocabulary. For others, deeper reasoning or greater independence with the text. Reading progress did not look the same for everyone, but it was visible.

What This Unit Taught Me

This unit reaffirmed several beliefs I hold about literacy instruction for multilingual learners and teaching generally.

Mandates matter, but quality backward design matters more.

The Science of Reading provides direction. Teachers determine whether that direction leads to meaningful learning.The Science of Reading and ELD are not at odds.

Language development is not extra. It is foundational to reading for multilingual learners.Secondary multilingual learners need complexity, not simplification.

Their success derives from accessibility, not lowered expectations.Assessment should reveal thinking, not just accuracy.

For multilingual learners especially, reading growth appears in explanation, connection, and clarity.AI is here and needs to be acknowledged and integrated appropriately.

This requires instruction, reflection, and restraint (for students and teachers).

Moving Forward

If the Science of Reading is going to serve multilingual learners, especially in secondary classrooms, it must be applied with nuance, flexibility, training, and trust in teacher expertise.

The goal is not compliance. The goal is literacy. That means finding the gold at the heart of mandates and reshaping it for the students in front of us.

Hochman, J., & Wexler, N. (2017). The writing revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades.

Satrapi, M. (2007). The Complete Persepolis. Random House.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97-110). New York: Guilford Press.

The Reading Rope: Breaking it all down. (2023, June 23). Amplify. https://amplify.com/blog/science-of-reading/the-reading-rope-breaking-it-all-down/